Carlos Garaicoa (Cuba), installation view of Familia (Family), 2023. Capilla Museo de la Medicina. Venue of the XIV Bienal de Cuenca. Photo: Salomé Velasco.

by SALOMÉ VELASCO

Cuenca, in the southern Ecuadorian Sierra, is a city in which the conservatism of a society deeply rooted in religious beliefs coexists relatively peacefully with rapid modernisation. This modernisation is the result of the increasing number of foreign visitors. Alongside Ecuador’s capital, Quito, and Guayaquil, Cuenca is one of the country’s most important economic and cultural centres. It has about 15 museums and more than 50 churches, 17 of them in its historic centre, which was declared a Unesco world heritage site in 1999. This year, the city is hosting the 16th edition of the Cuenca Biennial, which is said to be the second most important biennial in Latin America, after São Paulo. This year’s edition, titled Quizá Mañana, is curated by the Argentinian-born Ferran Barenblit.

Museo Municipal de Arte Moderno. Venue of the XVI Bienal de Cuenca. Photo: Courtesy of Fundación Municipal Bienal de Cuenca.

The exhibition, which opened on 8 December last year, runs until 8 March and includes 29 projects, with 34 artists as part of the official selection and 17 Ecuadorian artists forming parallel official exhibitions. This new category is of great significance, considering that the director of the Cuenca Biennial Foundation, Hernán Pacurucu, was one of the co-producers of a 2007 event, A Propósito de la Bienal de Cuenca, which proposed a space for dialogue and debate regarding the “institutional, curatorial, municipal and bureaucratic criteria and mechanisms related to the artistic and cultural scene and circuits”. From this proposal, a parallel platform, called Cuarto Aparte, was born in 2009, which was a nucleus of artistic management and production that aimed to create spaces where art could be democratised. According to its founding members, Cuarto Aparte sought to democratise art, given that the biennial’s founding members had responded to the elitist and restrictive nature of art. However, Cuarto Aparte never saw itself as an anti-biennial project.

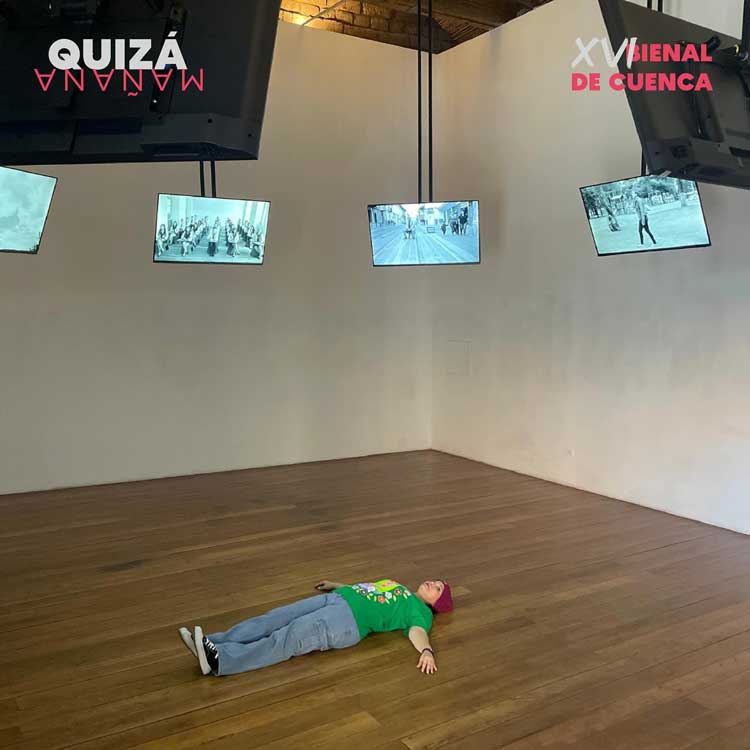

Alexander Apóstol (Venezuela). Installation view of Ser latino es estar lejos (Being Latino is being far away). Photo: Courtesy of the Fundación Municipal Bienal de Cuenca.

Even though Pacurucu was not a member of this collective, he shared similar ideas, which are reflected in Pacurucu’s current management: he refers to an “open-door biennial”, and aims to promote the aesthetic thinking of Ecuadorian art. He emphasises his intention to democratise art in the city through various strategies. These include editing and publishing five encyclopaedic volumes on contemporary Ecuadorian art, installing murals in strategic places in the city, the implementation of a sculpture forest, a permanent art research centre, and the creation of an exhibition space for the art collection amassed in the 36 years of the biennial.

Patricio Palomeque (Ecuador), installation view of La suma de los círculos (The sum of the circles), 2023. Photo: Courtesy of Fundación Municipal Bienal de Cuenca.

For this 16th edition, Quizá Mañana proposes a reflection on present conflicts, focusing on Latin America and the Russia-Ukraine war. Barenblit says this exhibition is “politically very brave”. In the curatorial statement, he describes Cuenca’s Biennial as a meeting point, a “mood” from which it will set something in motion, and whose existence, in turn, responds to the city that sets it in motion. While the previous pedagogical model of the biennial failed to attract an audience outside the artistic community, the biennial has become part of the city’s collective imagination and is now embedded in people’s memories. This continuity has sustained the project since 1987 and serves as a reference point for young artists.

Rosa Jijón (Ecuador), installation view of Vertical, horizontal, las figuras del poder (Vertical, Horizontal, The Figures of Power), 2023. Photo: Courtesy of Fundación Municipal Bienal de Cuenca.

The biennial now attracts local people and those from abroad, including artists and art students, local businesses and tourists. This is unsettling for local cultural managers and artists who share contradictory perspectives regarding the biennial. For some, says Pacurucu: “[This institution] has been responsible for dividing those who know and those who do not, those who understand from those who do not, generating tensions, elitism, and intellectual structures in an exercise of power to discriminate against the other.”

The new administration, in office for the last five months, aims to address the shortcomings of previous administrations, moving away from the pedagogical model and bringing in fresh forms of local support. One of its proposals is to change the statutes of the biennial so that at least 40% of participants are from Ecuador. Pacurucu points out the precariousness faced by the country’s artists, which is evident in the limited number of exhibitions of their work held annually in museums and galleries, and the fact that artists themselves are required to cover the expenses and logistics required for each show.

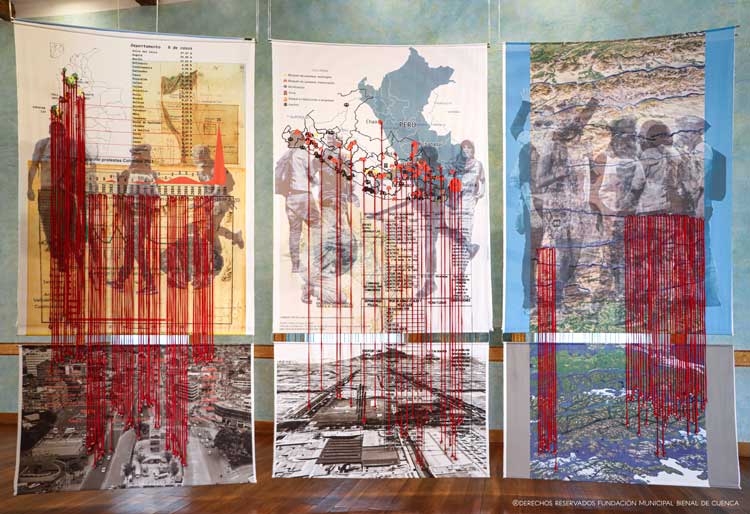

Valuspa Jarpa (Chile). Installation view of Cartografías de la Sindemia (Cartographies of the Syndemic). Photo: Courtesy of the Fundación Municipal Bienal de Cuenca.

For that reason, perhaps, on non-official circuits, art moves between “craft” and “outsider art” in spaces that are sustained thanks to self-management. This is the case of La Mata de Frío Azezino, a space that started as a blog by Joaquín Pérez, a graphic designer and painter. A year ago, the artist decided to transform a space at his home into a gallery and two workshops, where emerging artists can exhibit their works and make use of the creative spaces. Its focus is primarily on hip-hop culture and urban art. The openness that the itinerant members of the collective maintain allows them to diversify into alternative artistic expressions, including murals, graffiti, painting, fanzines and stickers. This facilitates the commercialisation of their work and enables them to become known without having to conform to the restrictions of the city’s conventional galleries. In this sense, Pérez says, La Mata is a “safe place”.

Joaquín Pérez (Ecuador). Kyoto OG, 2023. Oil, acrylic and spray paintings. 480 x 100 cm. Photo: Visión sin fin (Endless vision).

Another gallery that stands out for its controversial theme is El Prohibido, owned by Eduardo Moscoso. For 25 years, this cultural centre has been dedicated to the spread of “extreme art” and neo-gothic aesthetics. Images related to death and the demonic in various media, including pencil on paper, acrylic on canvas and wood sculpture, cover the shelves, the ceilings, even the bathrooms, as well as underground passages that Moscoso has created as part of the tourist experience. This space generates controversy because it exists in a primarily conservative culture, and because it exposes the scrutiny and censorship to which artistic expressions are subject in the city. In March last year, at the local branch of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, Moscoso exhibited The Temple of Arutam, a work that mixes elements of Shuar and mestizo culture in a sculptural series showing Christ breaking free from the cross in three pieces. For the sculptor, the work creates syncretism between nature, the mystical, the pagan, the religious, social denunciation and reality. However, many citizens denounce his work as blasphemous and satanic and there have been several attempts to close down El Prohibido.

Gabriela Andrade (Ecuador). El Caballito (The little horse), 2023, 40 x 50 cm. Paisajes imposibles (Impossible landscapes) photography exhibition. Official Parallel Exhibition, XVI Bienal de Cuenca, 2023. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

For María Gabriela Andrade, a visual artist from Cuenca, censorship is the result of fear of the unknown. She believes the key is the artist having the right approach and generating a dialogue with the spectator. “When the work flows from you naturally, perhaps the other receives it in the same way,” she says. She also believes that the function of artists is to open the minds of people. She says the important thing is not to yield to social and political pressure, but to focus on the work. With the local artistic circuit being limited and closed, it is easy to succumb to that controlling culture. She defends her work in its mere existence, saying that, despite having felt underestimated for being a woman, that is not her point of interest. She adds: “These are situations that happen, even in the art world, those parameters exist.” Andrade points out that, as an artist, what matters is perseverance, and only through constant work can an artwork gain a place and establish a name for its author. She also says that while Cuenca is a traditionalist city, the possibility of travelling and exploring spaces virtually has given young people a greater openness to new works of art. However, this openness is limited by the demands of contemporary times and the idea of economic success, which is why young aspiring artists lean towards creative careers that fit better into the labour market.

From a holistic perspective, art in Cuenca is in a precarious state, forcing artists to diversify. Having multiple jobs seems to be a non-negotiable condition, with teaching being the main economic source and, in many cases, the one that sustains their art production. In the words of Pacurucu: “The artist is an artist thanks to the fact that he stops being an artist.”

Amalia Pica (Argentina), installation view of Aula Grande (Big Classroom), 2023. Photo: Courtesy of Fundación Municipal Bienal de Cuenca.

Pacurucu strongly believes that the biennial should act like shockwaves in its surroundings. Then, it should extend to nearby neighbourhoods and finally reach the entire city. Rather than being seen as an event that happens every two years, it should aim to energise the culture in a city that has traditionally given significant weight only to craftsmanship and religious art.

The World Crafts Council proclaimed Cuenca a World City of Crafts in 2020, recognising its trades such as goldsmithing, jewellery, pottery and ceramics. These practices originated from pre-Inca cultures (Cañaris) and, with the influence of the conquest, they acquired greater refinement, to the point where their production became important enough to trigger a commercial boom in the 1950s, mainly due to the export of toquilla straw hats and gold mining. Today, there are still neighbourhoods known for the trades practised there, such as Las Herrerías (ironwork), El Tejar (tiles) and Convención del 45 (pottery). These activities have an immediate impact on the city’s aesthetics, where a sense of belonging to tradition and beliefs persists, a characteristic shared with most cities in the Ecuadorian Andes. This invokes the influx of foreigners who settle in the city, leading to a phenomenon of gentrification in heritage areas, changing the traditional dynamics of the city.

Darwin Guerrero, Elefante (Elephant), from the series Juguetes/ de lo ingenuo a lo perverso (Toys/ from the naive to the perverse), 2023. Elastic thread, metal mesh, kraft paper, variable dimensions. Photo: Salomé Velasco.

In this context, Pacurucu sees the biennial as a way to promote a return to painting, “but no longer understood from a decadent and antiquated romanticism but as a reflection on painting, such as painting in the expanded field”. Danny Narváez, from the city of Machala, exemplifies this with his experiments with melted plastic colour to address plastic pollution. As does Darwin Guerrero from Cuenca with Proyección: Sol Naciente (2011), an installation that consists of the projection of digital photography on three RGB channels of Claude Monet’s 1872 painting Impression, Sunrise.

The discussion about the state of art in Cuenca is bittersweet. It could be summarised by the concise cultural policies that result in many artists having to pawn their belongings to cover the expense of producing and exhibiting their work. It is an environment where, eventually, everyone knows everyone, either through affinity or discord, where artists compete for limited spaces and public budgets for art. Despite this, a creative drive persists in the city that refreshes and reconciles the reason for the existence of art.

• The 16th Cuenca Biennial, Quizá Mañana, runs to 8 March 2024.