Jesse Jones, The Tower, installation view, Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Talbot Rice Gallery. Photo: Sally Jubb.

Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh (part of Edinburgh Art Festival 2023)

24 June – 30 September 2023

by VERONICA SIMPSON

There is a history of artists taking on the role of shaman. Joseph Beuys is the standout example, in his performative actions of the 1970s, with Marcus Coates assuming that mantle in more recent times. In his video work Radio Shaman (2006), Coates wore a smart suit adorned with dead animal pelts and a deer’s head placed over his own, telling the radio presenter: “I work as a shaman, and a shaman is traditionally someone who works with their community and helps solve problems that it’s very difficult to find solutions for.”

Jesse Jones eschews the outward garb of a shaman, but her installations have a strong whiff of spell-casting. And she certainly dives into difficult problems – namely, centuries of oppression and persecution of women. Her big moment came at the 2017 Venice Biennale when she represented Ireland with Tremble Tremble. This work evoked the injustices of the witch trials, the legal systems that men put in place to establish and perpetuate them, as well as conjuring primal myths of a female giantess via the striking, silver-haired figure of the actor Olwen Fouéré, who dominated the screen and the installation with her spine-tinglingly primal performance. The power of women and the lunatic/delusional tone of the texts used to describe and prosecute their annihilation were entirely self-evident without any additional verbal or textual clarification.

Part of Jones’s motivation to make the work was driven by escalating anger at the eighth amendment to the Republic of Ireland’s constitution, which declared abortion illegal. It would be hard to attribute the somewhat miraculous turn of events a year later to an artwork, but the amendment was formally repealed in 2018. Certainly, Tremble, Tremble played its part in reflecting the zeitgeist (and the Irish government made an official visit to the biennale work).

Olwen Fouéré, installation view, installation view, Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

The Tower, seen here at Talbot Rice Gallery and part of Edinburgh Art Festival 2023, is billed as the second instalment in what is promised will be a trilogy of works by the Dublin-based artist. As with Tremble Tremble, we are ushered into a dark, cave-like space (no small feat in the double-height, usually daylit main gallery at Talbot Rice). Fouéré is with us again, on two tall screens reaching the full height of the room.

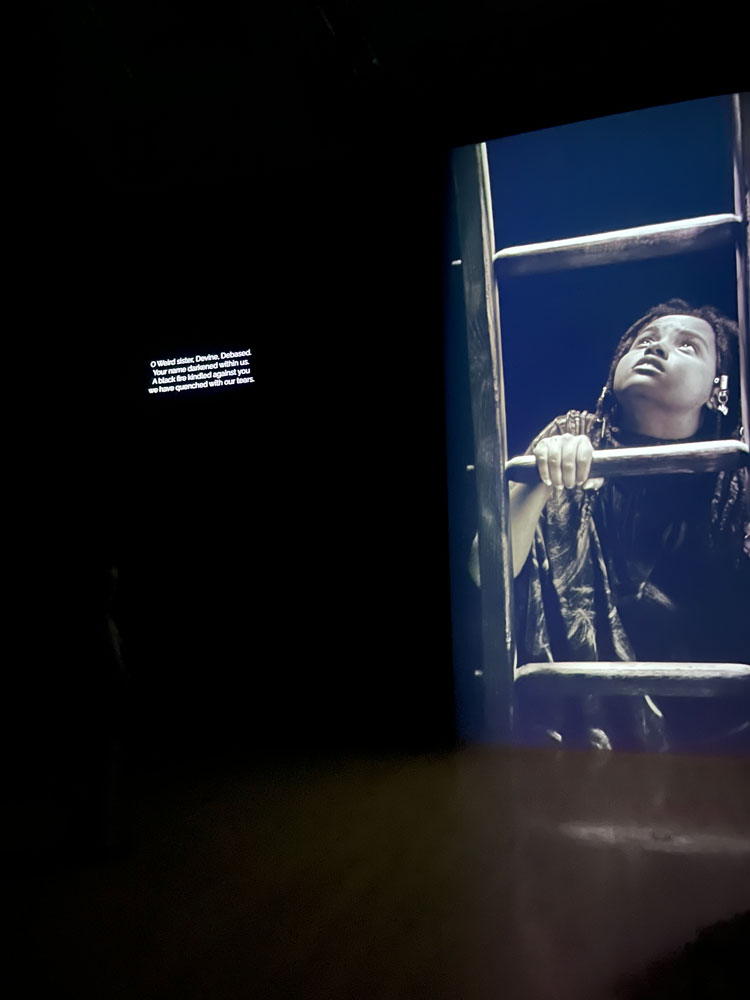

Jesse Jones, The Tower with luminous caption next to film. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

This time, she is sharing screen-time with a community of young women who sing and whisper phrases and incantations, staring up to the heavens, circling around each other, or lying in a dense, hairy pile, looking for all the world like a litter of pups. Fouéré is also represented in a beautifully sculpted statue, seated in the centre of the room. The statue, carved out of Portland stone, glows luminous like marble when spotlit from above (a theatrical lighting and curtain rig had to be installed in the gallery for this show and it is used to great effect).

Jesse Jones, The Tower, installation view, Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Talbot Rice Gallery. Photo: Sally Jubb.

The performance runs for 30 minutes but there is no “right” time in which to enter or leave, Jones tells us later. If you arrive, like I did, in one of the quiet moments focusing on the films, you, too, might be surprised when a spotlit, live figure is suddenly revealed in the corner: a young woman, clad in black, is crouching at the foot of a ladder propped up against the wall.

Jesse Jones, The Tower, installation view, Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Talbot Rice Gallery. Photo: Sally Jubb.

She tests the ladder, ascends a short way, slowly descends, and then circles the room, sweeping the curtain Jones has devised for this show around participating viewers to draw you into the central space with Fouéré’s seated, stone figure. At a specific signal, she produces a token and hands it to an onlooker. These tokens are part of the installation. Others are delivered via a large, carved stone aperture placed against a far wall. It lights up periodically, and human fingers poke through and drop another token on to the floor for eager onlookers to scoop up. These clay tokens have assorted figures printed on them. They also have a soft but distinctive scent.

Jesse Jones, The Tower, installation view, Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Talbot Rice Gallery. Photo: Sally Jubb.

Does any of that help in making sense of the installation? Not really. But it is spellbinding. At a talk on the opening night with the Talbot Rice Gallery curator, James Clegg, he asks her: “If Tremble Tremble was about the repeal of the eighth amendment, what is the moment for The Tower?”

Jones says she had been researching the Magdalene Laundries, primarily Irish institutions run by the Catholic church, in which young, “non-conforming” women (unmarried mothers especially, or prostitutes, but also anyone who didn’t conform to the restrictive behavioural codes for women at that time) were incarcerated as indentured labour. They usually stayed there for the rest of their lives. One of these institutions was in Glasgow, the Magdalene Institution for the Repression of Vice and Rehabilitation of Penitent Females, known locally as the Maryhill asylum. It was established in 1812, and girls as young as 15 were incarcerated here, sometimes for little more than being thought to dress immodestly. In 1958, a bunch of girls aged between 15 and 19 staged a breakout. They were rounded up but escaped again. According to a report in the Irish Times, this happened repeatedly over three days until officials from the Scottish home office visited to investigate. An inquiry was ordered, and the institution was shut down. As Jones says at the talk: “They committed no crime, they were never convicted of any wrongdoing. So, in essence, they had no right of appeal … There has never been an apology for the way these women were treated in Scotland as there was in Ireland.” (In 2013, Enda Kenny, the then Irish prime minister, formally apologised for the state’s role in these labour camps.)

Jesse Jones, The Tower. Girls clustered together with image digitally manipulated to appear as a kaleidscope. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Jones, having spent time during the pandemic reading and listening to the accounts of the now elderly women who had suffered in these institutions, wanted to pick up that story of systemic injustice, but make teenagers the focus of her work, tuning in to that “teenage energy”, as she says during the talk – especially the rebellious energy of the Glasgow women, and their bond as a group.

Rather than have the work relate these specific, historical narratives, she says: “I wanted to have a more embodied element.” Describing the installation and its choreography, she says: “Your whole body is taken over in a 360-degree spherical kind of space. And the experience is of being and sensing. A lot of the stories I’m telling … you don’t have to know all the things my work is talking about, but you can feel it, sense it … In the last couple of years, I have wanted to make work from the neck down: to think it and feel it but then allow it to flow.”

Jesse Jones, The Tower, 2022-23. Production still. Photo: Marion Bergin. Courtesy of the artist.

There are many powerful women woven into the script. Some of the incantations whispered by Fouéré and the lead young actor, Naomi Moonveld-Nkosi, are taken from the writings of Marguerite Porete (1250-1310), a mystic who wrote a seminal text on Christian mysticism, The Mirror of Simple Souls, which led to her being declared a heretic and eventually burnt at the stake; some of the incantations are said to be the last words of other women who met the same fate. Porete was a key figure in Jones’s research for this piece, as were the 12th-century abbess and composer Hildegard of Bingen and the anchorite Julian of Norwich. I read in the exhibition leaflet later that the aperture through which the tokens fall is meant to resemble a church “hagioscope”, or spyhole, through which people could see anchorites in their cells. Jones has created a sort of replica of this cell, in which a performer will apparently be present, visible to the peering eye, for the duration of the show.

Knowing this gives those words, that atmosphere, a powerful new charge. But none of it is clear to visitors when they first approach the gallery (unless they read the leaflet), nor is it otherwise articulated by the elements of the installation. Does the fact that most people won’t know any of this backstory deprive the piece of some of its potential power? Is it better to allow oneself to experience the heady mood of the combined elements, as it ranges from horror to ecstasy, experiencing it, as Jones suggests “from the neck down”. I guess that is up to the viewer, but I can’t help feeling that no explanations or clarifications were needed to feel the full impact and significance of Tremble Tremble. For all the evident skill in its use of sound (with sound design by Mark Murphy and a score by Irene Buckley), staged setting (by designer Róisín Gartland), cinematography (Emma Dalesman) and choreography (Junk Ensemble), it remains a collection of absorbing and emotionally affecting elements, rather than a coherent experience.

Having said that, I won’t soon forget that ecstatic moment where the young women are singing in exquisite polyphony, or the sense of struggle and submission that weaves between their enactments of intense, bonded community. The experience is so powerfully theatrical, and the inspirations behind it, ancient and modern, so intriguing and significant at a time of continuing denial of women’s rights in so many parts of the globe, that I found myself wishing she would expand it into a stage play. Who knows, maybe my wishes will come true …