Nanda Vigo, Ambiente cronotopico vivibile, 1967. Installation view Haus der Kunst, 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Haus der Kunst, Munich

8 September 2023 – 10 March 2024

by VERONICA SIMPSON

“Try to imagine you are in Japan in 1956. You are in a public park. You see children inside and around this large, suspended lantern, playing. Remember that there has been a major catastrophe in your country – one of the defining moments of the 20th century. What does it mean for a woman to make this completely different kind of artwork that has nothing to do with sculpture or painting, nothing like what has gone before? It means that the game has changed. That there is no need to believe in tradition … Now jump to the present and what is happening this moment? We have dictatorships, economic crises … and a real climate catastrophe. This requires a reaction from artists. It requires change.” With this stirring statement, Andrea Lissoni, artistic director of Munich’s Haus der Kunst, introduces a hugely ambitious and challenging show, recreating some of the pioneering environmental artworks of the 20th and early 21st century, all made by women.

Tsuruko Yamazaki. Red (Shape of Mosquito Net), 1956. Vinyl, wood, metal fixture, wires, bolts, light bulbs, 360 x 360 x 270 cm. Installation view Haus der Kunst, 2023. Photo: Agostino Osio.

That same suspended lantern of which Lissoni speaks hangs inside the first room. Tsuruko Yamazaki’s Red (Shape of Mosquito Net), from 1956, dangles off the floor, at just the right height to allow – even entice – you to bend and insert yourself into it. But, first, you must take off your shoes and slip them into one of the many numbered woven baskets that line the room, and you must read the instructions – the “score” as Lissoni calls it – on the wall, which he and the co-curator, Marina Pugliese, have composed. It tells us we must “feel comfortable” as we encounter the 12 artworks they have assembled, “which all require different behaviours. You can walk, you can sit, you can dance … you can experience freely.” Last, we are told: “Move through, around, observe … Become a cat.”

Red (Shape of Mosquito Net) first appeared in the Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition in a suburban park in Ashiya, Japan. Inspired, as the name suggests, by the shape of the traditional Japanese mosquito net, Yamazaki was evoking a space of safety, of slumber, of surrender – but in her use of the colour red, she was probably referencing the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, killing more than 200,000 Japanese civilians and laying waste to these cities. However, in her combination of this explosive, fiery colour and the playful, immersive and familiar form, as well as its park setting, the work speaks perhaps of healing. By all accounts, the structure was a magical sight at night – the park stayed open during the Outdoor Gutai festival – and was lit from within, so that it offered a double sensory pleasure, inside it and outside, animated by the shadows of its occupants.

Yamazaki was one of two founding female members of the Gutai experimental art group and studied with its leader, Jirõ Yoshihara. Their interest was in abstraction and going beyond traditional forms and materials. The placement of their assembled works in a public park for free encounter was unprecedented at the time.

The Gutai members were familiar with the work of Lucio Fontana, the founder of spatialism, who, in 1949, had coined the term environments to describe an artwork actively incorporating its audience. The Gutai group’s work was also appreciated in the west, appearing in artist Allan Kaprow’s 1965 reference book Assemblage, Environments and Happenings. Kaprow and Fontana are familiar names in the field, but Lissoni tells us that when he and Pugliese sat down to discuss a show on environmental art and started examining the main figures and works from the mid-1950s to the 60s, they found that many of the leading exponents were women, with works that had a huge impact at the time but afterwards went largely unacknowledged. Lissoni and Pugliese decided to put the record straight with this remarkable show, with additional curatorial input from Anne Pfautsch.

Aleksandra Kasuba, Spectral Passage, 1975. Mixed media: wood structure, neon tubes, nylon fabric, sound, 2370 x 1340 x 550 cm. Installation view Haus der Kunst, 2023. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Nearly 20 years after Yamazaki’s park art, the Lithuanian artist Aleksandra Kasuba created Spectral Passage (1975), a magical, almost hallucinatory sequence of voluptuous, rainbow-tinted nylon structures that fill the long hall beyond the first room at Haus der Kunst. There is something Alice-in-Wonderland-esque about moving from one rainbow-hued nylon vessel to the next. I found the experience even more enjoyable from the outside, as the tinted forms create luscious layers and blends of colour and form as you follow their contours. Kasuba created this work for The Rainbow Show at the De Young Museum in San Francisco, which explored the symbolism and significance of the rainbow in ancient mythologies and modern art. I am not sure how the work would take you on a “metaphysical path from birth to death and rebirth”, as the caption promises, or how it relates to Gustav Holst’s The Planets Suite, different movements of which are played softly inside each segment. But it certainly consolidated Kasuba’s reputation in the US, to which she had moved in 1947. She was a key figure in the environmental art movement, exhibiting her first such work, Contemplation Environment (1969), for the 1969-70 show at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York, and turning her Manhattan apartment into a live art environment with Live-In Environment, between 1971 and 1972.

The last, violet segment in the room sequence in the current show pivots sideways and deposits us in a history room, where several screens reveal something about the extraordinary deep dive that this show entailed. There is a video of Kasuba’s work being constructed, and there is a timeline, born of the research Lissoni, Pugliese and many colleagues conducted, revealing – true to their word – the dominance of female artists shaping this field. As it scrolls along all the key exhibitions between the 1950s and 70s, there are familiar male names: Dan Flavin, Fontana, Andy Warhol, James Turrell, Terry Riley, Robert Morris and Robert Rauschenberg. But there are many more women: Marta Minujín, Carla Accardi, Judy Chicago, Nanda Vigo, Lygia Clark, Laura Grisi, Tania Mouraud, Maria Nordman and Faith Wilding, all of whom appear in this show. Lissoni did not want this to be seen as a “tokenistic” show because it is all women, but because they genuinely were the ones making the groundbreaking work, and he is absolutely right.

The reason their names disappeared from the history books (aside from the familiar chauvinistic and western-centric take on art history) is that most of the works were ephemeral, disposed of immediately after the shows. Made without any concern for monetary value or collectability, few of them found their way into the archives, so most of the works here had to be constructed from scratch - not copies but recreations. Requiring three years of painstaking collaboration and research, they have been remade with all the necessary artist and curatorial input possible to ensure they are identical to the originals.

Marta Minujín, ¡Revuélquese y viva!, 1964. Wooden frame, fabric, paint, synthetic foam, 245 x 335 x 270 cm approx. Installation view Haus der Kunst, 2023. Photo: Agostino Osio.

For example, the Haus der Kunst team worked closely (albeit remotely) with the Argentinian Minujín to recreate her ¡Revuélquese y Viva! (1964), a chaotic and colourful cubic construction of stuffed limbs and torsos inspired by the mattress – the ultimate, everyday object. The work’s title translates as “roll over and live” and, as you crawl through its cosy spaces, it plays a soundtrack of Beatles songs, which would have been heard on radios all over the world that year. The upholstery material with which the work is made is painted with neon stripes after the finished sculpture is assembled. It is part of a family of Colchones, inhabitable structures Minujín made from mattresses and blankets after she returned to Buenos Aires from a sojourn in Paris in the 1960s, where she abandoned painting for Happenings (her first event was a bonfire of all her previous work).

Lea Lublin, Phallus Mobilis. Inflatable tubes, dimensions variable. Installation view Haus der Kunst, 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

There are two works by the Argentine-French artist Lea Lublin, both pneumatic inflatable structures from 1970 whose pretty pastel tones belie their political and provocative intentions. One, Phallus Mobilis comprises a forest of inflatable cylinders dangling from the ceiling, through which the visitor is invited to roam, knocking into these playfully suspended, featherlight, penile “balloons”.

Lea Lublin, Penetración/Expulsión (del Fluvio Subtunal), 1970. Inflatable plastic tunnel with props, 275 x 275 x 275 cm. Installation view Haus der Kunst, 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

The other is a 20m long tunnel, Penetración/Expulsión (del Fluvio Subtunal). It is a hugely enjoyable sensory adventure as you squeeze yourself through these translucent bubbles, encountering other smaller bubbles, as well as an entrance and exit that evoke bodily apertures: two tightly laced pink tubes that require some determined squeezing to get through (though a gallery assistant is on hand to help you into them, or prise you out). As Pugliese says while touring us through the exhibition: “Lea made these works in reaction against the fallocentric attitudes of the day, and political oppression.”

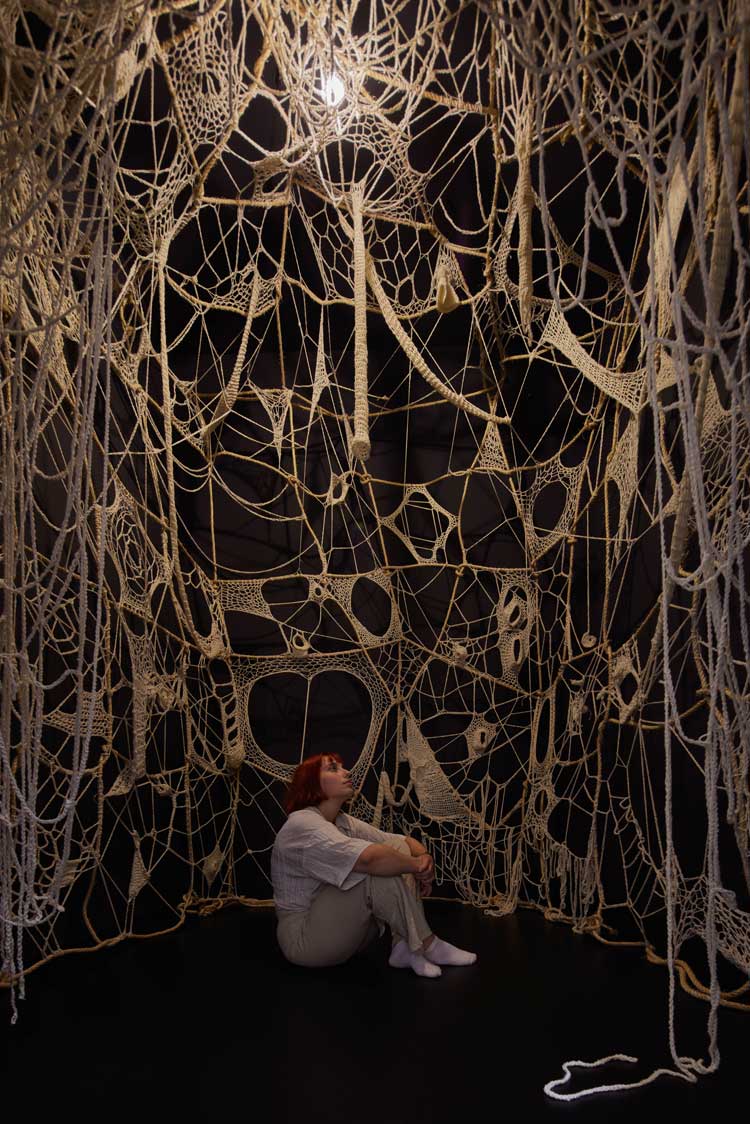

Faith Wilding, Crocheted Environment (Womb Room), 1972. Acrylic yarn and sisal rope, room (wooden structure), 274 x 274 x 274 cm approx.

Installation view Haus der Kunst, 2023. Photo: Agostino Osio.

A world reimagined by women was the context for Faith Wilding’s 1972 Crocheted Environment (Womb Room), produced for Womanhouse in Los Angeles, an art space initiated by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro as part of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Programme. Born in Paraguay in 1943, Wilding emigrated to the US in 1961 to study at CalArts, and subsequently taught there. This sisal crocheted concoction was inspired by the woven structures Wilding had seen in her youth, made of weeds and branches by indigenous Paraguayan women, and it celebrates that unsung women’s labour. It is one of only two works we are asked not to touch – though we can crouch inside the smallish room in which this webbing of soft threads has been conjured. The other is Tania Mouraud’s We Used to Know (1970-2023).

This uncompromising French artist has remade her 1970 work of tall lamps with projecting bulbs that heat to 45C, placed around a metal box (looking much like Doctor Who’s Tardis, but far less friendly), to incorporate updates in lamp technology.

Tania Mouraud, We used to know, 1970–2023. Stainless steel tower, heating lamps, rubber flooring, 422,5 x 515 x 381 cm. Installation view Haus der Kunst, 2023. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Entering the sealed space (two large glass doors close it off from the main gallery) and circumnavigating the central box is a distinctively unpleasant experience, although the repetitive soundtrack that plays inside the room is not quite as unpleasant to our 21st century ears, exposed as they have been to grime, death metal and techno, as Mouraud intended it to be when she devised it in 1970. Pugliese tells us that when helping the team to reconstruct the work, Mouraud said: “I didn’t make this piece for the audience. I don’t care what the audience thinks.”

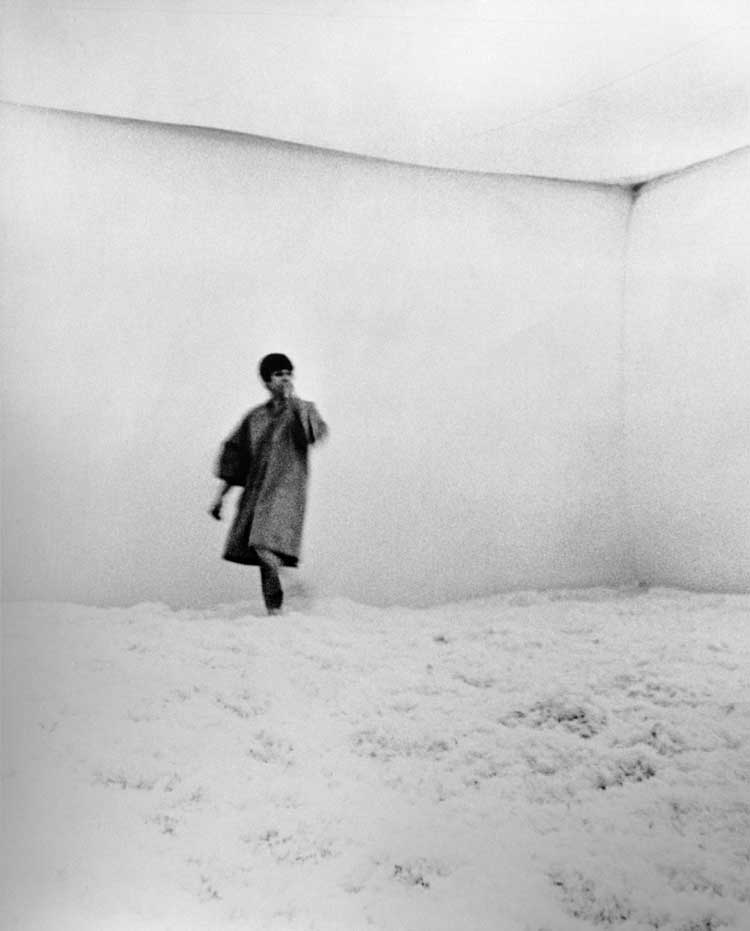

Judy Chicago, Feather Room, 1966. Room (wooden structure, diffusive canvas, 36 LED spots), filled with cruelty-free duck feathers, 775 x 658 x 400 cm.

Chicago’s Feather Room, located around a corner, is a far more whimsical and charming affair – literally a white cube, whose floor is buried a foot deep in pale feathers. Again, updated for the current times, we are told these are chicken feathers, sustainably and humanely harvested from free-range chickens. But when it was made in 1967, the intended impact of the work was far from fluffy. Chicago, who has filmed a comment for the show’s launch event, says: “It was my response to the male-centred land art and male-centred environmental art that was touted as the land art, the environmental art. I wanted to soften and feminise that manmade world.”

We encounter a far darker version of the feminine in Clark’s A case é o corpo: penetração, ovulação, germinação, expulsão (1968). You are guided into the black, fabric entrance aperture, fighting your way through a labyrinthine procession of spaces, with only the vaguest chinks of light to orient you. One room is filled with squishy balls (presumably the waiting eggs), another is filled with great masses of tangled, pale, hairy fronds. Just as claustrophobia threatens to overwhelm you, there is a full-height metal tube that seems to be blocking your exit – it has to be spun around to create a carousel, releasing you into the final section. You emerge relieved and a little dazzled.

These are all fascinating artworks, the job of assembling and recreating them as impressive as the works themselves, but not more so than the histories that are revealed – of the artists, the times they lived through, and the fact that it is only now that we are learning about their pioneering practices. As Pugliese says at one point: “The history of environmental art is a history of losses – not only the work, but the fact that their work often went unrecognised.” This exhibition makes a valiant effort to redress that imbalance, while also encouraging a spirit of change and possibility. Kasuba’s profound statement, reproduced on the wall near her work, seem fitting: “You must enter the unknown not by accident, but fully aware that you are taking a decisive step. Only then, you will know why you are where you are. Don’t fret. You won’t be alone.”