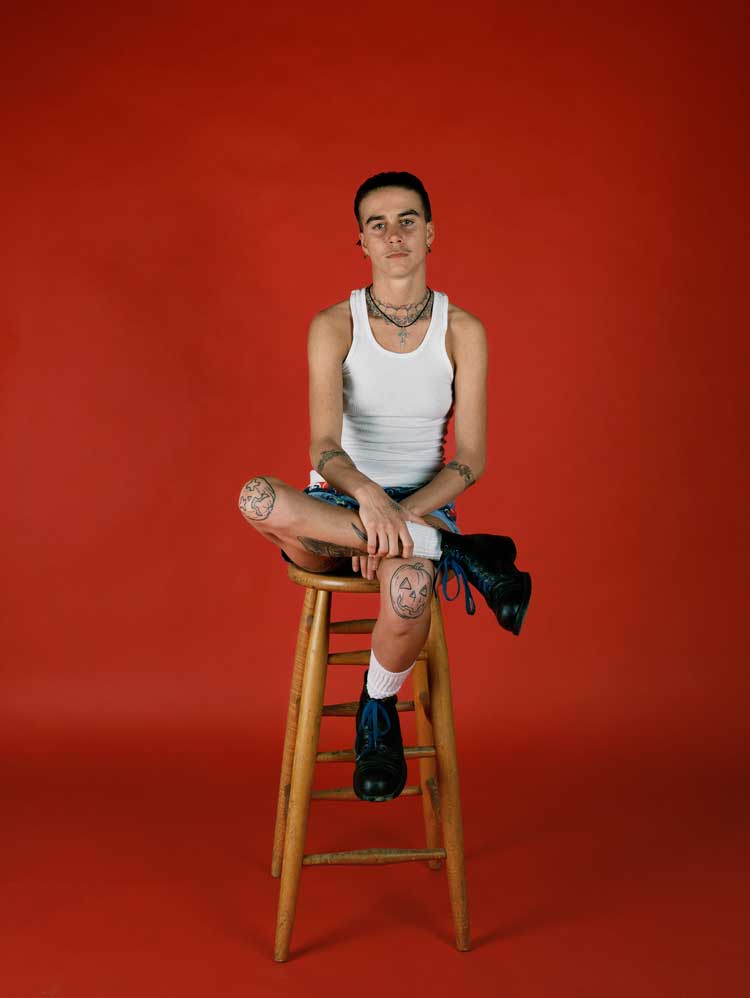

Catherine Opie. Photo: Heather Rasmussen.

by ANNA McNAY

The name Catherine Opie (b1961, Ohio) is synonymous with west-coast queer leather culture of the 1990s. Much to the photographer’s chagrin, people’s first thoughts are invariably still of her two self-portraits – Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993) and Self-Portrait/Pervert (1994) – for which she had images and words cut into her flesh, and, in the latter, her arms pierced with 18-gauge steel pins and her face hidden in a black bondage hood. It is not that she regrets these works at all, but that misinterpretations continue to be perpetuated. For her then, as now, the significance was the meaning of the blood in the language of those represented. In 1990s California, this spelled Aids, and her unflinching imagery still carries with it stigma and taboo; in the 2020s Vatican, well, it speaks of centuries-old violence in Christian dogma, nevertheless left uncensored for all and sundry to see. Thus, Opie travels full circle, arriving at her latest body of work, Walls, Windows and Blood, made during a residency at the American Academy in Rome in 2021 and conceived especially for Thomas Dane Gallery’s Naples location.

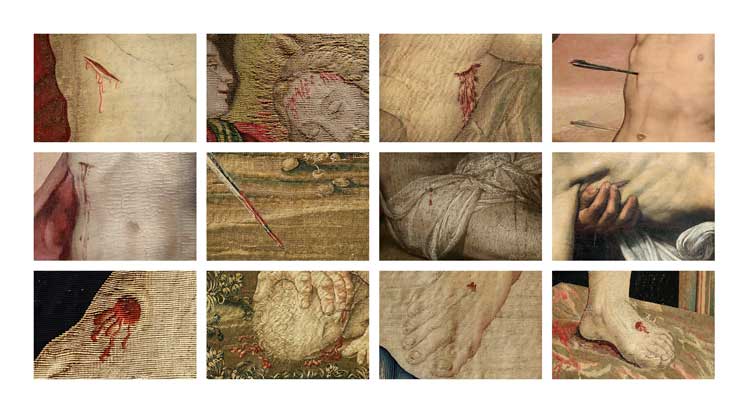

During her six-week residency, Opie was, thanks to the pandemic, granted unparalleled access to the Vatican, four days a week, to explore the architecture and ideologies represented within this, photographing, as her title suggests, Walls, Windows and Blood. The Blood component comprises images of bleeding bodies (and body parts) in the tapestries on display, which she has formulated into grids, which, she hopes, create a new kind of taxonomy and open up a fresh conversation.

Catherine Opie, Blood grid #4, 2023. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Opening up a conversation is all Opie, who says she has never strayed too far from social documentary, has ever really hoped to do, by offering a reappraisal, a chance to challenge our relationships with iconic buildings and all that they have come to mean, and a chance to “other” things that have perhaps only ever been considered under one mainstream light.

Opie’s exhibition opens just as the new school year begins, the first in more than three decades when she will not be teaching (she was latterly professor of photography at the University of California, Los Angeles). Instead, she looks forward to more opportunities to travel and make her own work without having to “hustle” to fit it all in. Her outlook on the current global situation, especially in the US, is not a cheerful one, but she is used to battling her way through life and is glad to now at least have a voice that can be heard.

Studio International spoke to Opie at Thomas Dane Gallery in London, during a trip she was making with her son. She reflects on her career – behind the lens and in the classroom, makes clear her passion for the medium, and shares some of her views on its place and role in the wider history of art.

Catherine Opie: Walls, Windows and Blood. Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples, 19 September – 18 November 2023. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: M3Studio.

Anna McNay: How and when did you get into photography, and how did your practice develop?

Catherine Opie: I started taking photographs when I was nine, and I really wanted to be a social-documentary photographer. As you grow with a medium, and as you teach it, you begin to question its specificity and your relationship to it in terms of trying to create a discourse around your life and the times you’re living in. Much of my work is really trying to answer my own questions and quandaries about sexuality, and ideas of architecture, our built environment and its relationship to humanity. How do we think about things, especially photographically, that we know are iconic, and how can we distil that iconography to allow for a different discourse? I think that has a lot to do with being queer and coming out and the times I have lived in. I was born in 1961, so being a mid-westerner in America at that time, and then moving to California when I was 13, really informed how I look at the world and what I want to portray. My work has always been made for everybody it represents, especially the early work around queer community. I needed to make that work because it was important for visibility. I have so many questions about what it is just to live in this world, which seems at times almost too hard to bear. The past five or six years have been fascinating for me. When Trump got elected, it was just so shocking. To go from the Obamas to that! And so the questions I have been asking have a lot to do with institutional structure right now. I guess it started with me making the film The Modernist, in 2017 [Opie’s first film, presenting a dystopic view of Los Angeles through a series of still images], and then going on to this new series of photographs, Walls, Windows and Blood, taken in the Vatican – a built environment that relates to the very specific identity and set of historical ideologies of the Catholic church, within which I am not even recognised.

_1.jpg)

Catherine Opie, The Modernist, 2017 (still). HD video with sound, 2 channel stereo sound, 21:44, looped. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

AMc: Before we talk about Walls, Windows and Blood and your forthcoming exhibition, can you say a bit more about The Modernist?

CO: The film is in conversation with Chris Marker’s radical photo-roman La Jetée, which was made in 1962, the year after I was born. Chris’s greatest fear at the time was nuclear war, because of the Cuban missile crisis. La Jetée uses still photography to tell a story of longing, time travel and the terror of nuclear apocalypse. And, to a great extent, that is what The Modernist is about as well. La Jetée is heavily nostalgic, whereas The Modernist is more about questioning how an artist is ever going to be able to live in LA. And so they start burning down houses – iconic, utopic, modernist houses – in relationship to the ideas of the haves and the have-nots. In 2019, movies such as Parasite came out, and I realised that I must have my finger on the pulse, in a certain way. Art is communication, communication of ideas across a broad range. But, beyond that, I am in love with the medium of photography and the aesthetic pursuits of what I can do within my medium.

Catherine Opie: Walls, Windows and Blood. Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples, 19 September – 18 November 2023. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: M3Studio.

AMc: Can you say a little about how you work? For example, do you work with analogue or digital?

CO: Both. I still shoot with an 8x10 camera here and there if I want to. Digital cameras are really great now, though. They allow you a certain kind of freedom, especially when travelling. Walls, Windows and Blood is shot with film and digital. I had about four cameras with me in Rome.

AMc: Do you do much post-production work?

CO: Not much. A little bit. I was trained with film, and I use digital cameras like film. I don’t Photoshop images or manipulate them in any way. It’s usually straight file to print, like how I would print a negative. I print everything in my studio. I have a 5,000 sq ft studio in LA, where I have scanners and three printers and a great big archive.

AMc: You had your first darkroom when you were 14.

CO: Yes. I built my darkroom with babysitting money.

AMc: Who showed you what to do?

CO: I was taking photography in high school, and my grandfather had a darkroom in his basement in Ohio, so I used to spend time with him, and when he shut down his darkroom, I got all his old trays and things like that. My uncle is a painter, but he was really into photography, too. And then there was a family friend in Ohio, who would take me into his darkroom. So, I had been around it, and everybody knew that I was really in love with photography, and so they allowed me to do it.

Catherine Opie, Dover, England, 2017. Pigment print, 61 x 40.6 cm (24 x 16 in). © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

AMc: What kind of things were you photographing back then?

CO: Much of what I photograph now. But I moved from Ohio to California at a very awkward age – the height of Barbie, just as it is in London right now – and I was a tomboy. I always had short hair and glasses. I wasn’t a girl-girl, I was a boy-girl. I started to take my camera to high school plays, where I would sit in the front row taking pictures. Then I would go home and print them in my darkroom, bring them back the next day, and give away 8x10 photographs. That’s how I finally got a group of friends. And it’s funny because that’s what I did with my early queer portraits, too. I felt like a geek, photographing all these really cool people who were part of my community, and so I gave them prints as well. It seems like that’s a theme with me – I tend to make friends through my camera.

Catherine Opie, Blood grid #4, 2023 (detail). . © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

AMc: Do you have a particular format that you prefer printing in now?

CO: Not necessarily. It depends on the body of work. With Walls, Windows and Blood, the walls are really interesting, because normally I do panoramas, as with the various American cities that I have made works about, but this time I worked vertically. So, they’re these long, thin vertical prints that are going to lean up against the wall. And they will be sitting on marble plinths that were specially designed for them. My question is: “Should these walls still be standing? Do they have the right to be there any more? And what are the walls for? Who – or what – do the walls protect?” There is certainly an idea of being protective of the pope and the Catholic ideology, but the pope doesn’t even live in the papal residence in the Vatican. He lives in a little room with nuns. This pope is a very different pope from previous popes. He really is more interested in humanity, but he also still has to uphold the doctrine of the Catholic church. He’s a very curious pope to me.

Catherine Opie: Walls, Windows and Blood. Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples, 19 September – 18 November 2023. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: M3Studio.

AMc: Are you a Catholic?

CO: No, I was raised an atheist. And one of the great things about being an atheist is that you’re not attached to any belief system, so you get to be more of a scholar.

AMc: How did Walls, Windows and Blood come about? I realise there have been many steps in between, but it’s still quite a leap from west coast queer culture to the Vatican.

CO: That’s exactly the hypocrisy of the world we live in. “Why would you photograph high school football, Cathy, when they were the kids that beat up all of us queers in high school?” Because they have the right to exist as well. Because if we’re talking about a greater relationship to humanity and understanding our culture and the time we’re living in, you have to be open to it all. And bearing witness, in my mind, is the ability to do it with an openness and a curiosity that allows you to critique it, but also allows you to potentially celebrate ideas of beauty within these institutions as well. Nothing is clear cut to me. I’m not interested in binaries. I want to open up dialogue. So, if the work can create a conversation, if the work can create a greater understanding in relationship to representation, then I’m happy. That’s my hope as an artist.

AMc: Can you say a bit more about the other aspects of Walls, Windows and Blood?

CO: Yes. Alongside the walls, I photographed every single window inside the Vatican. Windows, of course, raise issues of transparency, which is something we’re talking about a lot now, in relationship to every institution. As you know, I am also an educator. I just retired from UCLA after 25 years. I chaired the department there, so I did a lot of training about how to create a better community, a more inclusive community. For example, why don’t we have more female artists showing in museums when my graduate programme was 65% women? The windows were a way of mapping out the architecture, mapping out the space, but also about the relationship to the Vatican being a city within a city, with its own governance. There’s no other place like it – and the specificity of that was easy to break down to my own Holy Trinity of Walls, Windows and Blood.

Blood is the taxonomy. It goes back to Foucault talking about the order of things. This story [of Christianity] has been told for a very long time now, but what is our relationship to the story? What are stories? And what is our relationship to truth and story? These are really big questions. So, I focused on and framed images of blood leaving the body – the most iconic thing in every church throughout the world, because Christ sacrificed his body – and I created a grid, so it becomes a taxonomy, so to speak. It allows you to see certain moments of absurdity. In my case, as an artist, it is absurd that museums want to put a warning sign before Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993) [an early work by Opie, showing her back, with a child-like drawing – two figures in skirts, holding hands, standing in front of a house, with smoke coming from the chimney, and birds in the sky – carved into her flesh and outlined in blood], but children can wander through the Vatican and see tapestries depicting bloody knives stabbing through children’s brains. Like, what is that? The queer body can’t be seen, but this body of blood can?

.jpg)

Catherine Opie, Cathy (London), 2017. Pigment print, 83.8 x 63.5 cm (33 x 25 in). © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

AMc: There is a definite parallel between Self-Portrait/Cutting and the Blood grids.

CO: Exactly. There are only two self-portraits I made where I manipulated my body in that way: Self-Portrait/Cutting, which was made 30 years ago now, and Self-Portrait/Pervert (1994), 29 years ago. It bothers me that these are what have always been talked about and how my body has been seen. At the time, there was a lot was going on. Think about what blood meant at that point [towards the peak of the Aids epidemic]. Blood was killing my friends. Blood was scary. People pathologised these images, but you have to think about what the substance meant and did within our culture. That’s what I decided to do here. This is a language within their culture, but has it ever really been critiqued in relationship to the imagery? Creating these grids allowed a different kind of taxonomy, viewed through the architecture of the Catholic church.

Catherine Opie: Walls, Windows and Blood. Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples, 19 September – 18 November 2023. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: M3Studio.

AMc: You have mentioned that the Walls images will be displayed on marble plinths. How will the other works be installed in the gallery?

CO: When you enter the gallery, there’s a series of columns in the front room. The Walls images, which are about 6ft 4in [1.9 metres] in height, will lean in between the columns, questioning the structure of columns in the history of architecture. The marble plinths are being made in Italy. They were designed by Katy Barkan, a fabulous LA architect, who was also at the American Academy in Rome – she had won the Rome prize for architecture. I was thinking black marble, because of the stairs of the Vatican, but she had done a lot of research on marbles in Italy, especially ancient marbles, and she picked the veiny, blood-red marble. It really works.

Then you go through the rooms and there will be Windows and a Blood grid over a fireplace. Although this body of work was designed for the Naples gallery, it won’t be shown in its entirety, because there’s not enough room. In total, there are 14 Walls, 20 Windows and four Blood grids. I think all the Blood grids will be shown.

Catherine Opie: Walls, Windows and Blood. Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples, 19 September – 18 November 2023. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: M3Studio.

Then, in one room, all alone, there will be a large print of the pope, titled No Apology (June 5, 2021), which is the day on which he failed to apologise [on behalf of the Roman Catholic church] for the bodies of Indigenous children being found in [unmarked graves in] Canada [who had been abused and died in the care of church-run residential schools, in a system branded as “cultural genocide” by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission]. On that day, the body count was 65; it’s now grown to more than 1,200 children. The pope did end up apologising, going to Canada, doing a tour, and all of that.

AMc: Did you take the portrait of the pope yourself?

CO: Oh, yeah. I went every Sunday to listen to him in his little window. The image is really interesting because of the fact that he’s there in his little window. It’s the architecture of power.

AMc: And this – your time in Rome – took place during the pandemic?

CO: That’s the exciting thing about this body of work. It would never have been made if it weren’t for the pandemic. I had the rare opportunity of being able to go the Vatican four days a week, for six weeks, and to spend about four to five hours photographing [without crowds of people].

AMc: Did you have an idea of what you wanted to do before you got the residency? Did you have to make a specific proposal?

CO: I knew I was going to photograph the Vatican. I have done so much work on cities and the specificity of identity – that is my jam. I get so excited about doing deep dives into history in that way and trying to figure out how to talk about larger issues through really simple things. A window is a simple thing, but then what is a window really? I knew that I was going to photograph the Vatican because of it being a city within a city, and the theme of the American Academy that year was “the idea of city”. When I wrote my proposal for the residency, that’s what I said I would focus on, but I didn’t know that it would end up being Walls, Windows and Blood. I discovered that over the six weeks, and then editing at home. Usually, it takes a couple of years to make a body of work like that. I would print stacks of images in the studio, and then it’s a matter of figuring it out until it distils down to a place where you feel you have got something that is going to be interesting to put out in the world. I hope people think it’s interesting. I’m thrilled about it.

Catherine Opie, Pig Pen, 1993. Chromogenic print, 101.6 x 76.2 cm (40 x 30 in). © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

AMc: You have spoken before about using tropes from art history in your photography – for example, black backgrounds and/or chromatic colours for portraits.

CO: Yes, very much so.

AMc: Have you used any specific tropes for this body of work?

CO: I think it’s already art history. The tropes here are different because the work is bearing witness. Often, when I make abstract landscapes, they’re of completely iconic places; places which, in an Instagram age, have been photographed by everybody. And I want you to reimagine the relationship of place in the same way you have to reimagine your own hypocrisies. When I did the cliffs of Dover, for example, you were in the middle of Brexit, so what meaning was there in the relationship between this and an abstract photograph of the cliffs? Can the cliffs be othered?

AMc: You don’t approach your portraits any differently from your landscapes.

CO: No, I don’t. I think that a good portion of landscapes, as well as my cityscapes and architecture works, are also portraits. Portraiture, for me, is really the specificity of painting. People often say to me: “I love your paintings.” And I’m like: “You know, they’re photographs …” And they’re like: “Well, they’re very like paintings. Like, well, the lighting …” Yes, I’m good with lighting. I have spent my whole life with this one medium, so one would hope that I would know how to do it.

Catherine Opie, Untitled #15, 2017. Pigment print, 195.6 x 130.2 cm (77 x 51 1/4 in). © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

AMc: You have said before that photography can create a history which painting cannot. Can you explain what you mean by this?

CO: Well, it creates the relationship to documentary. If a person is Idexa or Pig Pen in 1993 [two of Opie’s friends and collaborators, shot as part of her Portraits series (1993-97), depicting individuals and couples from queer leather communities in Los Angeles and San Francisco], then that person is Idexa or Pig Pen in 1993. When I photograph them now, their bodies have changed. A painting will never have that specificity, because one will always imagine that the painter could have embellished or imagined. When I’m using a large-format camera, every single cut or part of the body is represented with precision. I might be using ideas from Holbein, or thinking about the relationship to the history of portraiture, but that is still bearing witness in my mind. It’s still a document. My work never strays far from documentary photography. Even if I have abstracted a landscape, it’s not truly an abstract photograph, I have just racked the focus as if I had taken off my glasses and couldn’t see clearly. It is still that place at that time on that day under those conditions. I love that about photography. It is a way to create a history of representation, and I’m completely attached to that. I don’t really want to make a photograph through a computer, because then you could embellish it. Don’t we have enough world problems right now in terms of AI? I’m so tired of looking at my Facebook feed, and all these photographer friends of mine are having a blast making imaginary photographs with AI. I have absolutely no interest in that. The world is vastly fascinating, and I want to spend whatever time I have left creating conversations for us through making images.

AMc: As you say, everything in photography is specific to the time and place it was made, even if it is more abstract. Yet the conversations can carry over different times.

CO: We have been in the same conversation for centuries now, haven’t we? I mean, do you think religious wars are going to end? We are a really flawed species. I don’t think we’re special – in fact, at times, I’m pretty horrified by us. I read a lot of dystopic sci-fi, a lot of Kim Stanley Robinson, Joan Didion and Susan Sontag, trying to philosophise and look at our relationship to the time we’re living in. I just hope that, somehow, I can be part of a larger dialogue, because I think we’re highly flawed, and I’m really concerned. I live in a city that has 55,000 people living on the streets. It is unfathomable to me. Just because I like aesthetics, and I like making really pristine photographs, doesn’t mean I think that life is pristine in any way.

Catherine Opie, Crater Lake, Oregon, 2020. Pigment print, 127 x 84.6 cm (50 x 33 1/2 in). © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

When I had my mid-career retrospective at the Guggenheim in 2008, it was called American Photographer. It was so much about the specificity of who I am, where I grew up, my family, etc. I have tried to make other bodies of work outside of America. I photographed in Venice for six weeks and tried to have a conversation about Venice and its specificity of this time in relationship to the history of Canaletto paintings. But this [Walls, Windows and Blood] is the first time that I feel I have been able to make a universal body of work that extends beyond my own identity as an American.

AMc: What is it about this body of work that makes it different and allows it to succeed?

CO: The relationship between photography and tourism is so deeply entwined, and to get to know a place, and to get to know some of the more complex relationships of place and identity, you have to break out of that. The Vatican is obviously one of the largest tourist sites, but [thanks to the pandemic] I was able to go beyond that, which was a really different experience from trying to think about Canaletto and Venice. A Canaletto painting is a Canaletto painting. I can make really beautiful photographs of Venice, but they’re not doing anything. The only thing that touched on being interesting in relationship to Canaletto was when the large cruise ships came up the Grand Canal and dwarfed the architecture. That was the only thing close to letting me talk about the now versus the history. It really feels amazing for me to have gone somewhere and realise that I can have a more extensive conversation. I’m hoping it will open up the ability for me to wander throughout the world in a different way.

Catherine Opie: Walls, Windows and Blood. Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples, 19 September – 18 November 2023. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: M3Studio.

AMc: Do you have anywhere specific at the top of your list to visit?

CO: Norway is next. I have been going to Norway for more than 10 years, and I really like it there. I’m obsessed with winter in Norway, and I’m obsessed with the colour blue. There is this hour and a half around one o’clock in the afternoon in the winter, where it’s not dark any more, but it’s that deep dusk. I’m going to try to photograph blue fjords in relation to climate change. I have really great Norwegian friends, including the explorer Erling Kagge [the first person to reach the “three poles” – North, South and the summit of Everest]. Now he does really curious explorations. He explored the underground sewer system of New York City, and then he walked all of Sunset Boulevard in three days. He has become a close friend, and he’s a really amazing guy. He wrote the most beautiful book about silence you could ever read in your entire life. And he’s a great collector. Hopefully, I can grab him to go up north, and he can show me some perfect blue mountains. I used my last 10 weeks of school making clay blue mountains, and glazing them, to start thinking about the blue mountains of Norway. At 62, I’m becoming heavily poetic! Maybe that’s just the way that I’m dealing with the other anxieties of living; reaching deep into my own visual poetry.

AMc: When you were teaching – apart from when you were making clay mountains – what did you teach? Was it more the technical side of photograph, or the aesthetics?

CO: I teach technical, because I’m a pretty technical photographer, and I like to geek out on it. I rebuilt a wet lab at UCLA over the past three years, to get people back in the dark room. The 18-year-olds want physicality again. They want to work with clay, they want to sculpt, they want to use their bodies and their hands. We have gone so far into this world of just tapping on a screen that this generation coming up is like: “Oh my God, look at this! This is magic!”, seeing the photograph come up in a tray of developer. I do critiques, as well. A student hangs their work up, and then the whole class and I talk about what’s going on in it. If I feel that I can make them better technically, I will say: “Hey, you should try this, this and this.” But I was a teacher who always taught from their content, not my own content. I can teach about why I think about the world the way I think about it, but that’s not how they’re thinking about it. I wanted to always teach from what was brought before me. I’ll miss it. It’s kind of weird to think I’m not going back this September.

AMc: What will you fill that gap with?

CO: Making my own work! No, I mean, that’s the crazy thing, right? Thirty-two years of academia, and only one year’s sabbatical. And in all that time I have been able to work, raise a child, have a successful marriage – until it just ended – and put a generation of artists out there that I have incredible respect for. If you can lead a life in that way, that’s fantastic. But a good friend of mine passed away last year – the artist Silke Otto-Knapp – and she was only 52. I taught with her, and she was such a brilliant painter. With that and the pandemic and everything else, you take stock of life, and you say: “OK, if I have 10 more years left, do I want to spend my time still teaching three days a week and then hustling in between time to make work?” And I realised no, I’m actually ready to pass it on to the next person. Financially, I don’t need that job any more. I should pass it on to the next generation. That’s only fair. That’s humanity. Nobody is as important as the next person.

AMc: Not everybody thinks that way.

CO: No. That’s the problem with the world. It makes me so upset. I’m surprised I’m not just in a heap weeping most of the time. I have had a lot of fights in my life, a lot of battles. And I’m happy that I have a voice to be able to lend out there. It’s intense to be in my country right now. America’s really a mess.

AMc: So is the UK.

CO: Yes, but such a large number of states not allowing women to have control of their own bodies is just appalling. And what’s going to happen with the supreme court in my lifetime? I don’t feel very positive for my son and my grandson. They’re both boys. That’s nice for them. But what’s going to happen to women? So, there we are, that’s a bit deep and dark. We can talk about something else now!

AMc: OK. If someone were looking at your work without any prior knowledge, what would you want them to get from it?

CO: People often just enjoy how the aesthetics work. They think it’s pretty.

AMc: And that’s OK with you?

CO: You can deep dive if you want to, but most people who go to a museum and look at art are just wanting to understand the world visually. You can read a lot of interviews, a lot of writing by art historians, and understand where I’m coming from, or you can just really appreciate the craft that I put into my work. That’s what is important to me. Sometimes people come up and say to me: “You’re a portraitist. You should be doing cities.” I just laugh. I mean, what am I really? I’m all of it! I’m actually all of it. I’m not going to be a singular identity.

• Catherine Opie: Walls, Windows and Blood is at Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples, Italy until 18 November 2023.

Click on the pictures below to enlarge