,-2023.jpg)

Bernard Cohen, Come Morning, 2023 (detail). Acrylic on linen, 105 x 145 cm. © Bernard Cohen, courtesy of Flowers Gallery.

Flowers Gallery, London

6 – 30 September 2023

by JOE LLOYD

The paintings of Bernard Cohen (b1933) are not obviously narrative. The London-born artist’s recent works, six of which are being exhibited at Flowers Gallery for his 90th birthday, are large-scale abstracts in acrylic paint. Some of them, such as Fox Heads – Seen in London (2023), are coruscating explosions of primary colour, a pop palette applied to a slippery, difficult-to-parse subject. Others, like Fool’s Home (2020-21), present a complex series of intersecting lines and squares covered with stripes and spots. There is a lot for the eye to rest on. The painting’s black-and-white composition cools down the work’s busyness a little and invites you to look for logic in the lattice. But for the uninitiated it might be difficult to find.

Bernard Cohen, Fox Heads - Seen in London, 2023. Acrylic on linen. © Bernard Cohen, courtesy of Flowers Gallery.

Yet Cohen is adamant that his paintings have a storytelling capacity. “My paintings tell stories,” he has said. “Sometimes a single canvas will tell a number of stories.” This has been a through-line across a career that spans seven decades. In 1966, he was one of five artists who represented Britain in the Venice Biennale, in a lineup that included Anthony Caro and Robyn Denny. Reviewing the exhibition in Studio International, David Thompson wrote: “Bernard Cohen uses the word ‘narrative’ about his own method, stressing that painting is a process in time and employing his continuous line as a kind of image for this continuing process.”

Many of Cohen’s stories are about the technique of painting itself. His paintings in the Tate collection include In That Moment (1965), in which a single line squiggles around the canvas in ever-changing colours, creating shapes that often seem to resemble human torsos. Matter of Identity I (1963), also in the Tate, is composed of “panels” resembling individual drawings and photographs. Some of the images are abstract, some representational. The overall effect resembles a pinboard covered with inspirations.

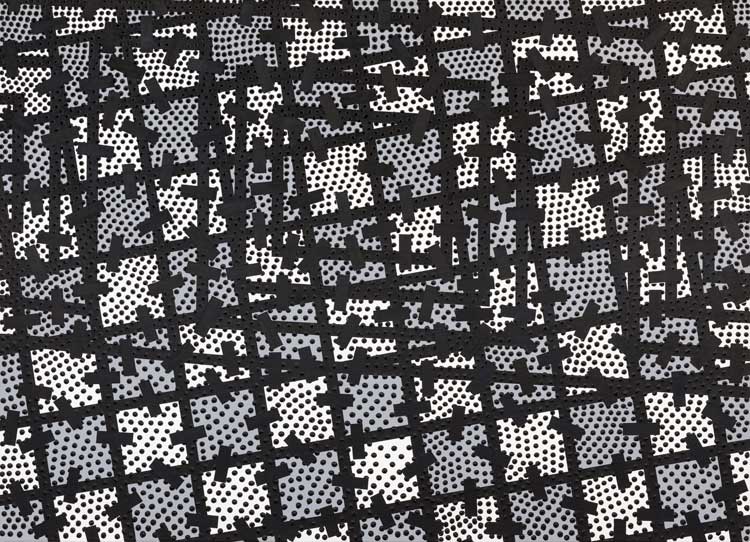

Bernard Cohen, Portrait of a Painting, 2021. Acrylic on linen, 105 x 145 cm. © Bernard Cohen, courtesy of Flowers Gallery.

Cohen uses very varied means, including spray guns and his fingers, to apply paint to his canvases. His works seem to ask us to wonder at how they were made. “[They] tell a story,” continued Thompson, “told by the painter about the painting itself, and the ‘ambiguity’ of the final result lies in the whole tissue and history of possibilities explored along the way – some carried through to a conclusion, others started but then altered and perhaps buried beneath the accretion of subsequent layers of linear activity.” Cohen’s most recent paintings see a simplification and emboldening, so that these lost layers and loose ends are harder to perceive. Whereas many of his 60s works played with the representational, and his work of the 2000s featured intricate complex web-like patterns, in the 2020s Cohen uses thick black lines, limited colour palettes and repeating units.

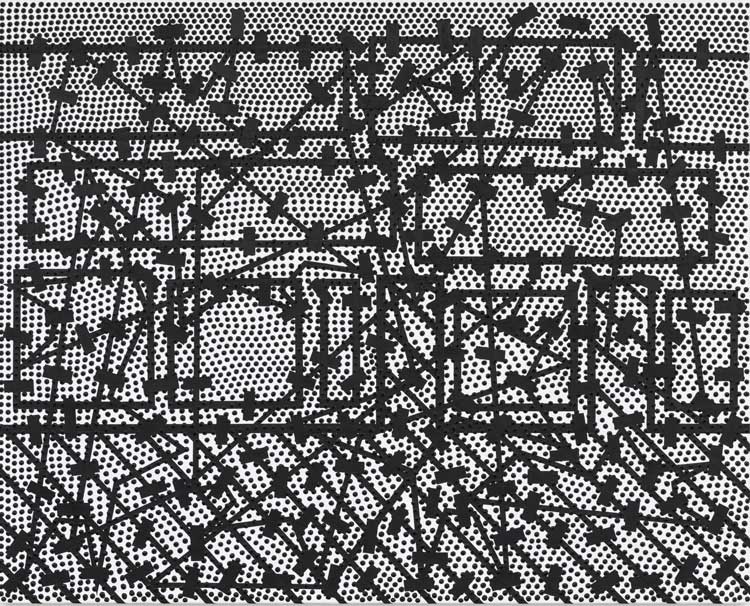

Bernard Cohen, Fool's Home, 2020-21. Acrylic on linen, 101.5 x 127 cm. © Bernard Cohen, courtesy of Flowers Gallery.

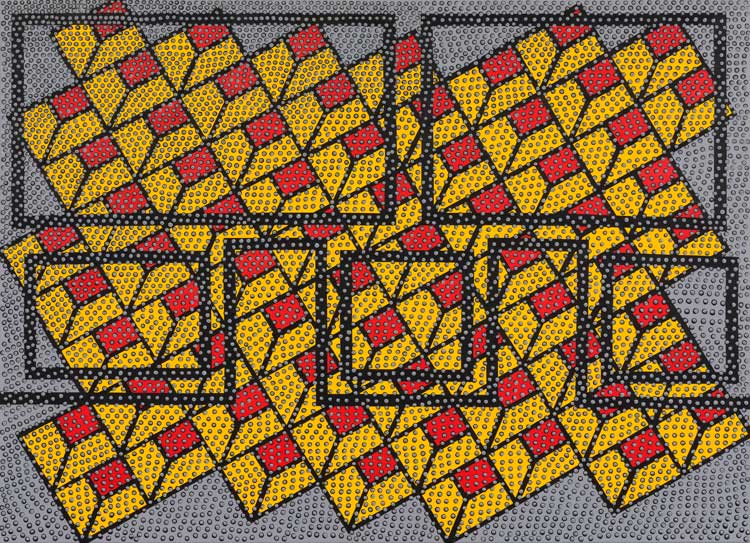

Some of the new works reference art’s past. A trio of paintings, the aforementioned Fool’s Home, Light After Dark (2022) and And Scatter (2022), reference the composition of Diego Velázquez’s elaborate Las Meninas (1656). Velázquez’s painting invites the viewer into a fully realised space. Cohen constructs a framework of black lines that echo the structure of the Spanish masterpiece, but then collides them with other patterns. In the case of And Scatter, these are squares of yellow and red shapes that seem to rise up out of the canvas like frustums. Cohen seems to be asking us to consider the physical space that his canvas and its paint occupies, as we might the illusionistic space of old master paintings. Which feels more real, and which more artificial?

Bernard Cohen, And Scatter, 2022. Acrylic on linen, 105 x 145 cm. © Bernard Cohen, courtesy of Flowers Gallery.

Two celebrated sequences cast a more general influence on Cohen’s work. In his 20s, he spent two years in Paris, where he was enraptured by two of the city’s artistic treasures: the Sainte-Chapelle, a 13th-century gothic masterpiece that survives from the city’s former royal castle, and Claude Monet’s eight Nymphéas (Water Lilies) at the Musée de l’Orangerie. Cohen was particularly struck by how the chapel’s stained-glass windows, which recount the Book of Genesis, are divided by strips of lead. This both spotlights the story and disrupts it, placing it into bedazzling patterns that sometimes seem to overwhelm the images; viewed from afar, the windows can look almost abstract. The Nymphéas, meanwhile, revealed to him a universal view of nature, rendered in what he describes as “a seemingly relaxed and loosely applied web of colour”.

Of these two cardinal influences, it is the former that has the most overt influence over these recent works. As Cohen said in a 2015 interview with Saturation Point: “I’m more influenced these days by the stained glass than I am by the painting because there’s no brushwork getting in the way.” All six works at Flowers are divided by black strips of various shapes and sizes, which resemble the lead strips in the Sainte-Chapelle windows. The fragments they create seem like shards of glass, particularly in the case of Fox Heads – Seen in London.

Bernard Cohen, Light After Dark, 2022. Acrylic on linen, 105 x 145 cm. © Bernard Cohen, courtesy of Flowers Gallery.

There is also an element of nature observation here, suggested by the names of the two works Come Morning (2023) and Light After Dark. The first depicts a grid of square units slightly askew; each of these units features three quadrilaterals, one red and the other two a different colour. The bright but restricted palette recalls that of medieval stained glass, whose creators relied on a small repertoire of colours. And like those windows, Cohen’s paintings are an expression of light, filtered not through glass but the will of their painter.