Drawing Room, London

25 September – 29 November 2014

by HARRIET THORPE

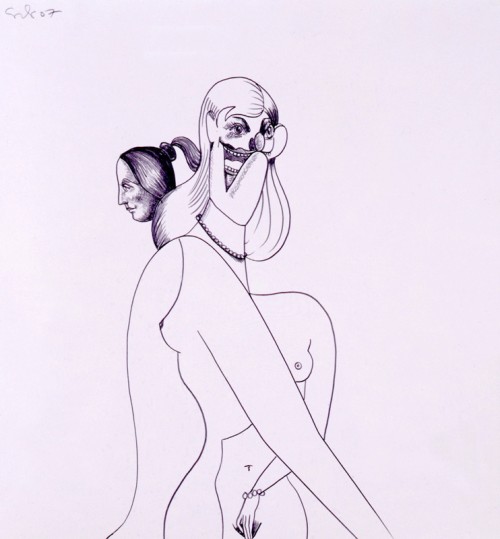

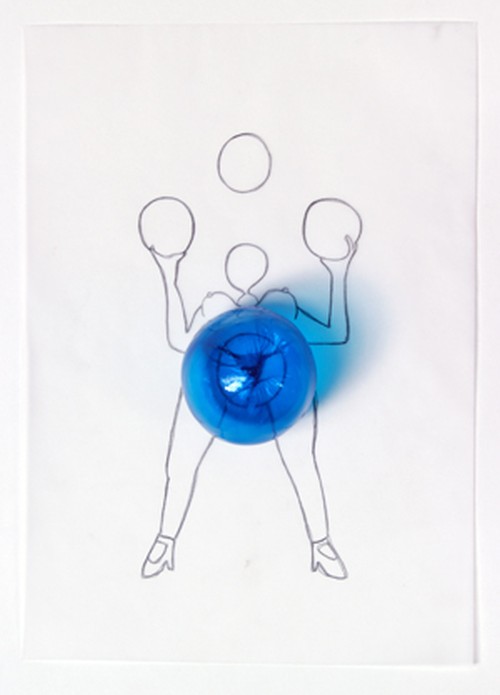

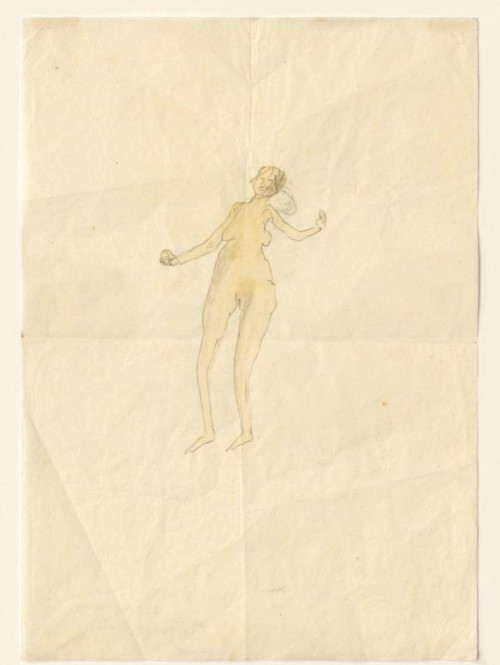

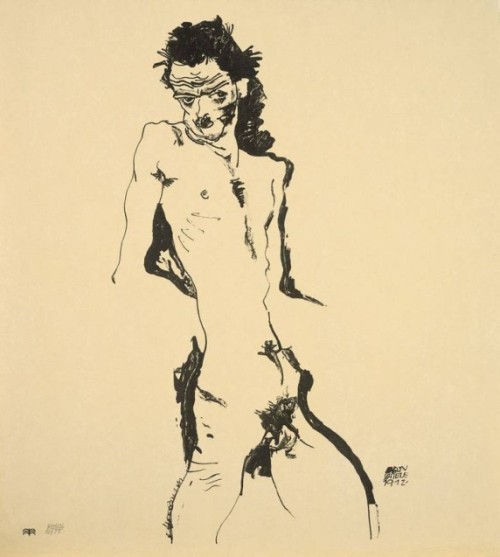

A lithograph by Egon Schiele opens The Nakeds at the Drawing Room, a group show of drawings from 23 artists focusing on the naked body. However, while Schiele (1890-1918) is seen as an influential starting point for the exhibition, his work is considered alongside other artists from the postwar period to the present day, and the show includes new work made specifically for it by Enrico David, Stewart Helm, Chantal Joffe and Nicola Tyson.

Schiele’s drawings challenged traditional depictions of the nude by exposing imperfections, vulnerabilities and desires, feelings that are recognisable in the artists’ works in the show. Yet although comparisons can be made, the contemporary works are differentiated notably by a shift of gaze relevant to the contemporary politics of today.

A conversation between the curators, London-based artist David Austen, Gemma Blackshaw, associate professor in art history at Plymouth University, and Drawing Room co-directors Kate Macfarlane and Mary Doyle, uncovered some of the themes surrounding the works. The exhibition began with a conversation between Blackshaw, who is an expertise in Viennese art from the 19th and 20th century, and Austen, about Schiele’s relevance to contemporary artists. Austen concluded that there is little evidence to show that he has been directly influential, but he is part of an artist’s education. “Schiele is so inimitable,” said Austen. “He’s an artist’s first crush – they’ve got their Taschen book hidden under the bed. Rosemarie Trockel [one of the artists featured in the show] says her mum gave her a book on Schiele when she was 20.”

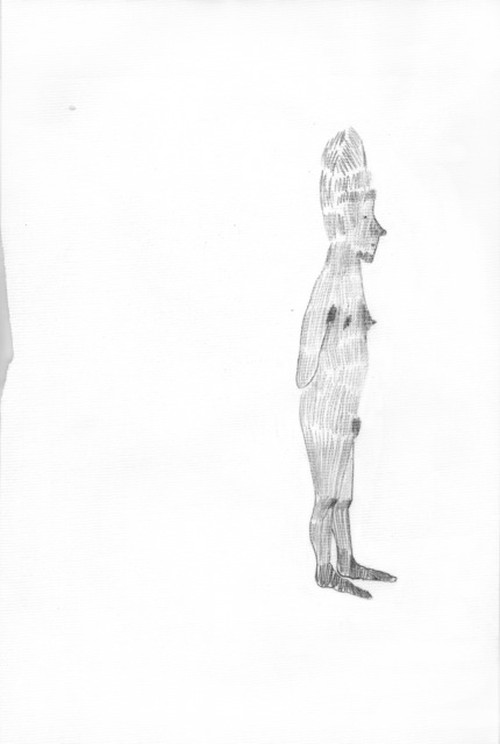

The artists selected for the exhibition are all strong characters and many of the works, like Schiele’s are instantly recognisable. “They are all maverick, independent and have taken their own paths. They’re all idiosyncratic,” said Macfarlane. Austen continued: “You’d like to go to a party with them all. There are no schools here – which was the fun of it.”

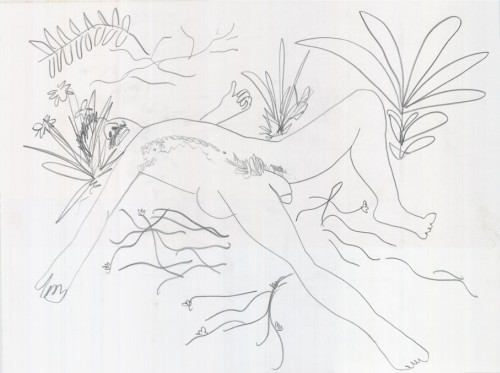

Austen proposed the title “The Nakeds” before anything else. “For me, there is a real shock of nakedness that there isn’t with the nude,” he said. He compared it to seeing nakedness in a Pier Paolo Pasolini film: “Like you’ve seen a naked figure running through a wood. It reminds you of a wild animal, that fleeting glimpse.”

Blackshaw described the curatorial process that followed: “Initially, I thought, how might we draw this line from Vienna in 1900 through to the 20th century? Starting off with Schiele, moving then to the 1950s and 60s, to the Viennese actionists with artists such as Arnulf Rainer, and then to the contemporary, to Tracey Emin, who openly declares how indebted she is to Schiele’s work. But it was far more creative to think about poetic relationships between works and to juxtapose the work of artists who would never usually share wall space.”

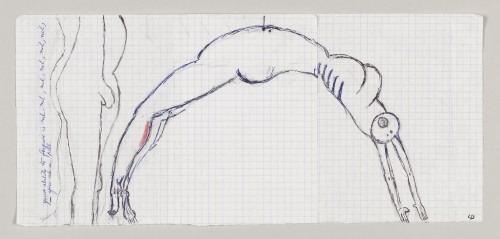

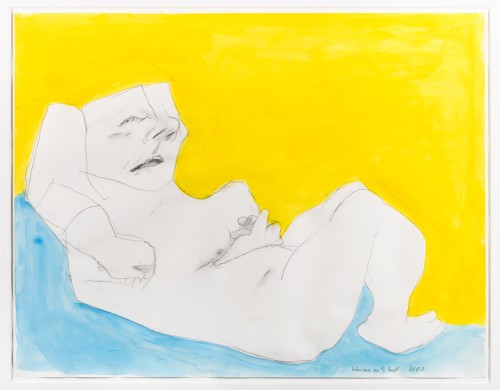

“We were thinking about how Schiele approaches the figure – the isolation, the unusual angles,” said Austen. “The figures are not surrounded by drapery and vases and all the things that soften nakedness. In a book of Maria Lassnig’s letters and diaries, she says ‘backgrounds are bourgeois’ – so she just gets rid of them, and talks about the sense of freedom she feels when she ditched them. Yet just because the backgrounds are empty, doesn’t mean they are empty. The figure activates that space to make you feel what it’s like to have consciousness inside a body. Enrico David talked about the ‘trauma’ of being inside a body. That’s a strong theme that runs through all of the works.”

For Blackshaw, the lack of “mechanics” of the studio in Schiele’s drawings, such as the board, easel or artist’s materials, give his works a timeless nature, appealing to contemporary generations. “We know Schiele worked from life models in a studio, but we don’t often see the signifiers of those spaces,” Blackshaw explained. “Although the drawings are very much part of Vienna in 1900, you don’t have these markers of a 19th-century interior, so his figures are isolated from their time, and you could be looking at a contemporary body.”

Austen also saw markers of modernity in Schiele’s work, while discussing the show with some of the artists involved. He said: “Marlene Dumas says Schiele’s figure looks more modern now, like the figures you see in magazines. I think the influence is very much in photography.”

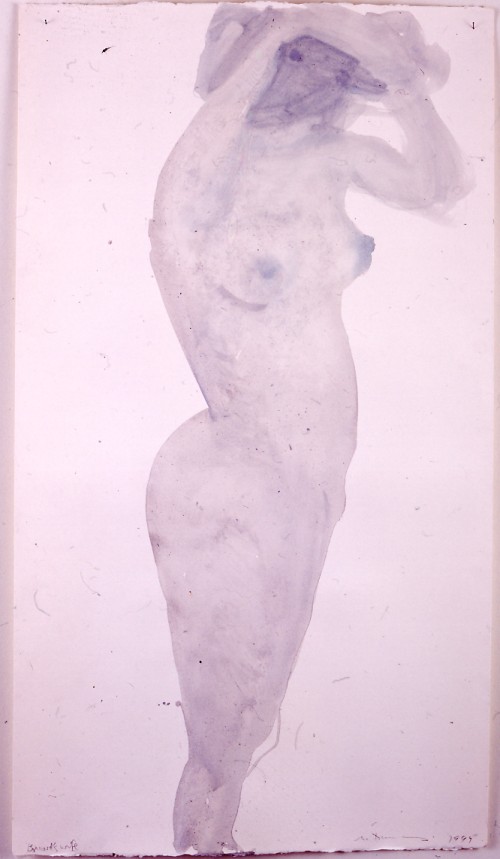

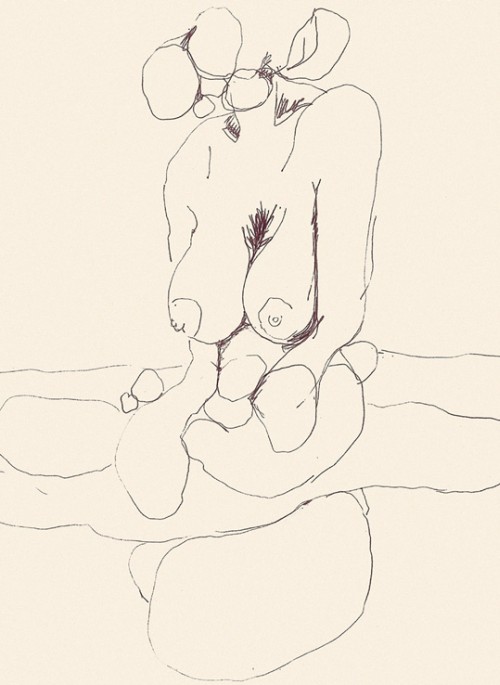

According to Blackshaw, the two Schiele works on paper, Male Nude (Self Portrait) (1912) and Standing Female Nude (Valerie Neuzil) (1912), weren’t the most obvious pieces to include in the exhibition. She said: “The two works in paper are portraits, as well as studies of the body. Even though the faces are differentiated and seem individual, the drawings are more about the human condition. You wouldn’t instantly recognise them as Schiele’s. They don’t have that very determined line, a line that Nicola Tyson described as being ‘colonising’ – it wants to own, to possess, to mark the perimeters of the territory. Those drawings don’t do that which is intriguing.”

Macfarlane described Schiele as “almost imagining being a woman in a woman’s body” in these works. Which Blackshaw noted, too: “He makes his face look like Wally’s face [Wally was the nickname for his girlfriend, Valerie Neuzil]. He gives himself a much fuller, bigger mouth, a real pout, and he’s stretching back, reclining, taking on the language of the nude. His genitals are flattened and compressed; they look more like the female genitalia than male. There is a real experimentation of him trying to relate with Wally.”

In a vitrine, there is also a rare set of lithographs from drawings done by Schiele in around 1920. They have an interesting backstory, says Blackshaw. “The owner, who was going to disseminate the prints, was arrested in 1923. He was acquitted, but almost all the prints – there were nearly 200 of them – were destroyed by the church. The fact that there are some remaining, and we have them here, is a real coup for the exhibition. Schiele was always on the cusp of what was and wasn't legal.”

Austen said: “It would be impossible for a male artist to behave like Schiele now. That’s why so many of the artists in the show are women: there’s a subversion that can go on, a turning over of the male gaze.”

Doyle mentioned Chantal Joffe, who works from pornographic images in magazines. She explained: “In the life-drawing class, Joffe couldn’t get the model to pose or do what she could find in a pornographic magazine. Those images informed the angles she adopted in representing the figure.”

Blackshaw replied: “It’s interesting how women artists and photographers have taken up that representation of the female body. It’s like they’re reclaiming it. It was so much part of the male modernist tradition and they’re transforming it.” Blackshaw has recently started some new research on Schiele in the context of pornography in Vienna in 1900. In her essay in the catalogue, she brings into question how Schiele was treading a line between controlling and emancipating women, taking advantage of their working-class condition, while liberating them sexually.

Macfarlane mentioned Tyson, who finds difficulty accepting Schiele’s gaze, addressing him in a letter – now published in the catalogue for this exhibition, but originally from the book Dead Letter Men (2013), in which she wrote letters to all the great male modernist artists from art history. “Although Schiele was someone that she, and so many people identified with, she finds his work problematic as a woman artist and rejects what he does,” Macfarlane said.

The life drawing class is many artists’ introduction to drawing the naked body, a tradition that Schiele has in common with the contemporary artists in the exhibition. Blackshaw said: “There are wonderful photographs of Schiele as a student at the academy in Vienna. He was incredibly young, 14 or 15, in a class with much older pupils, in a huge room where the life model is standing up on a stage, leaning on blocks in a classical thinker pose. Schiele is there in his suit. It’s this enormous, formal, stiff environment. When he left the academy at 18 or 19, he continued with that life drawing process in his studio where he was able to choose his own models. There were many impoverished life models working for artists in Vienna, who were also connected to the photographic pornographic industry and to prostitution.

“Suddenly this opened up a whole new way of representing the body that was not about a formal academic life drawing class. This was something different, sexual. One of the many reasons why Schiele appeals to so many artists, particularly in those early formative years, is because Schiele rejected that decorum.”

Contemporary artists in the exhibition have also diverted the traditional ways of drawing the nude. Macfarlane picked Fiona Banner as an example: “In Banner’s Double Door Nude (2004), she actually invited a stripper to come to her studio. The work is a written description of a private show. She has done a whole series describing a nude in writing, rather than drawing. Her choice to create wordscapes rather than depict the human figure is crucial in terms of her handling of early representations of women; she was always part of the show.” Austen added: “Her words are quite aggressive. When you read them, they feel very similar to following a Schiele line.”

A sense of contemporary discomfort or awkwardness is a feeling that can be detected in the works. Austen called it a vulnerability. “We all have that antennae. The insecurity of the new century that looms ahead of us, as it was then in Vienna, and also the insecurity of war. Schiele had the first world war. We have God knows what’s going to happen over the next few years.”

Blackshaw agreed, detecting a popular renewed interest in Schiele: “That’s another reason why we started with Schiele. He conveys so effectively these themes of exposure, violence, vulnerability, sexual excitement, longing, in a really economical way. It feels as if there’s a real interest in sex, death and desire in Vienna in 1900 at the moment. There is the exhibition Egon Schiele: The Radical Nude at the Courtauld [which runs until 18 January 2015] and there is also a new exhibition at the Freud museum called Freud and Eros: Love Lust and Longing [which runs until 8 March 2015].” A Tracey Emin exhibition titled Just me and Egon Schiele is also scheduled to open at the Leopold Museum in Vienna in 2015.

Intense, uncompromising and unconscious, this exhibition detects a brewing feeling of contemporary discomfort and uses Schiele to spark an upheaval. Insecurity, pain, desire and vulnerability are exposed in opposition to a culture that markets the body as a perfect form. These artists’ works re-humanise the body. Schiele did it at the beginning of the 20th century and The Nakeds does it now, at the beginning of the 21st century.

• The 23 artists featured in The Nakeds are: David Austen, Fiona Banner, Joseph Beuys, Louise Bourgeois, George Condo, Enrico David, Marlene Dumas, Tracey Emin, Leon Golub, Stewart Helm, Chantal Joffe, Maria Lassnig, Paul McCarthy, Chris Ofili, Carol Rama, Egon Schiele, Nancy Spero, Georgina Starr, Alina Szapocznikow, Rosemarie Trockel, Nicola Tyson, Andy Warhol and Franz West.

.jpg)