Jerwood Gallery, Hastings

11 June – 1 November 2015

by ANNA McNAY

Mention LS Lowry (1887-1976) and most people will picture grim, industrial cityscapes from Britain’s north-west, with smoke-belching factories; men bent nearly double, hastening along crowded pavements; grey drizzle; and children playing in the street. But Lowry was as inspired by the coast as he was the city. “Some people like to go to the theatre,” he once said, “some like to watch television. I just like watching ships.” But it was more than that which attracted the solitary artist to the open expanse of the North Sea. “It’s the battle of life – the turbulence of the sea. I have been fond of the sea all my life, how wonderful it is, yet how terrible it is. […] It’s all there. It’s all in the sea. The Battle of Life is there. And Fate. And the inevitability of it all. And the purpose.”

As part of the Jerwood Gallery’s Festival of the Sea, a small gem of an exhibition comprising 17 pictures – oils on canvas and board; watercolour; felt tip and pencil drawings – showcases Lowry’s intense relationship with the ocean. Spread across two small, dark rooms – which echo the mood of the works – visitors gain not just an overview of an aspect of the artist’s work that is usually overlooked, but also an intimate insight into his character, thoughts and self-perception.

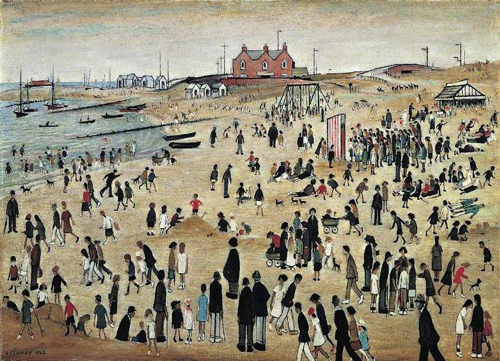

The first room features eight works, five of which are more recognisably Lowry. The earliest painting, a large canvas called July, the Seaside (1943), contains all of his hallmark ingredients: men with hats and sticks, women with prams, and dogs. The characters from his urban paintings appear simply to have been transported on a daytrip to the coast. But 20 years later, by the time he painted Beach Scene, Lytham (1963), Lowry’s style had changed: the paint is much thicker, applied on board rather than linen, and there is scumbling and clotting, as if the surface had been washed over by the waves and marked with the sediment of sand. The figures are indistinct behind a white spumous veil. The viewer looks on from a distance, not transported into the hubbub and fray.

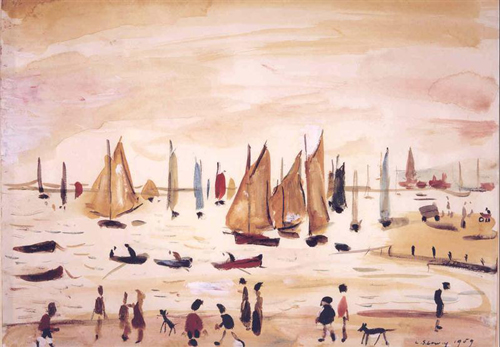

Seemingly at odds with the busy-ness of his beach-scene compositions, Lowry once said: “Generally, I put nothing on the sea when I paint it. Perhaps a tiny boat if I must.” Yachts (1959) is thus an exception on two counts: first, the harbour is about as crammed full of colourful sailing boats and kayaks as it could be, and second, watercolour was a rare medium for the artist who noted that these paints didn’t really suit him, since they dried too quickly and weren’t flexible enough. Whether or not Lowry valued his efforts, this is a delightful picture, full of spirit and charm.

In the second room, things are a little bleaker. Two deserted seascapes contrast strikingly with one another: the larger, Seascape (1965), calm, grey, damp and misty. The line where the sea meets the sky is horizontal and flat. There is an expansiveness to the view, but it is neither enticing nor compelling. The water seems feeble, lacklustre, void of enthusiasm. Grey Sea (1970), however, is smaller but so much more full of life. In this painting, unrecognisable as a Lowry as we know him, the vigour of the crashing waves sucks you in, the scratch marks on the surface of the paint reflecting this violence – a cruelty of nature meting out the suffering of life. A dark blackness marks water meeting sky, with rays of white light, a storm, bursting out of the void. Even the swirly floral gilt frame reflects the whorls of the waves. This is a miniature masterpiece that held me intent, and I defy anyone not to be swept away in its depths.

Three drawings opposite show a childlike side to the artist, comic, yet simultaneously sinister. Woman on a Promenade (1972) exemplifies Lowry’s late-career “grotesques”, a solitary, disfigured and darkly cloaked character, looming towards the viewer, semi-caricature, semi-threatening. The similarities to the dark hulk of the steamer in Ship Entering Princess Dock, Glasgow (1947), hanging across the room, cannot be missed. Black, tall and ominous, set against a bright, white light – a clear symbol for death.

Tall dark shapes and threatening objects populate Lowry’s coastal cartography. A drawing of a shark swallowing a man is said to represent the greedy, all-consuming art world indiscriminately eating him up, while further figures wave helplessly as they drown. In the distance, again, sailing boats bob along. Are they carrying the lucky ones to safety? Or are they oblivious passersby? More cynically, perhaps they are potential saviours, unwilling to stop and help. After the death of his mother in 1939, Lowry lived alone for almost 40 years and often spoke of his loneliness. Referring to some sea paintings inspired by a trip to Anglesey, Wales, in the early 1940s, he once said: “I started to paint the sea, nothing but the sea. But a sea with no shore and nobody sailing on it. […] Look at my seascapes, they don’t really exist you know, they’re just an expression of my own loneliness.”

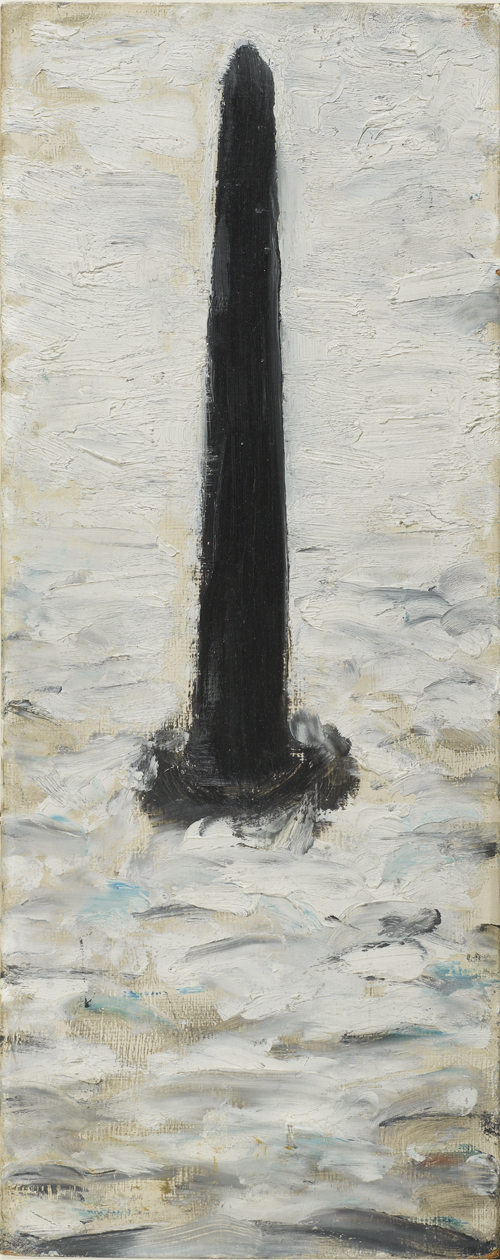

In a similar vein, Lowry painted a self-portrait, on display here: Self-Portrait as a Pillar in the Sea (1966) – “a tall, straight pillar standing up in the middle of the sea, waiting for the sea of life to finish it off”. One could argue that the thrusting black pillar, emerging from a foamy white ocean, be read as phallic. That may also be true. At the age of 88, Lowry professed to “never [having] had a woman”.1 He spent his life, it would seem, waiting: waiting for love, waiting for companionship, waiting, ultimately, for death. Perhaps this sheds new light on the overcrowding of his peopled scenes – after all, one is never as lonely as when in a crowd. Speaking about life and art, Lowry said: “I spent my whole life wondering what it all means. I can’t understand it, don’t understand it at all, can’t see any point in it myself. Still, there it is, you keep on working, and you keep on wondering what it all means, and it goes on and on and on and, there you are.” Similarly, speaking of the sea, he said: “What interests me here, of course, is the vastness of it and the terribleness of it … I wonder what would happen if the tide didn’t turn, and the sea came on and on and on and on. What would the place be like, and wouldn’t it be wonderful to see it?” No wonder, given his outlook, that the sea was such an apt metaphor for the battle of his life.

Reference

1. Hidden LS Lowry drawings reveal artist’s erotic stirrings by Roya Nikkhah, the Telegraph, 16 October 2010.